The effects of climate change are all around us, and for those of us who work in the energy industry, not a day goes by without thinking about what’s needed to enable a successful energy transition while also meeting growing demand.

Extreme weather, record temperatures, and rapid ice melt soak up a lot of ink in media headlines today.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) released an updated version of its Net Zero Roadmap in September, renewing its perspective that humanity can reach net zero emissions targets by 2050, as well as limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

It’s going to be a heavy lift to accomplish both feats, however, as the IEA says greater ambition and implementation, along with stronger international cooperation, will be critical to reach climate goals.

“The pathway to 1.5°C has narrowed in the past two years, but clean energy technologies are keeping it open,” said IEA Executive Director, Fatih Birol. “The good news is we know what we need to do, and how to do it.”

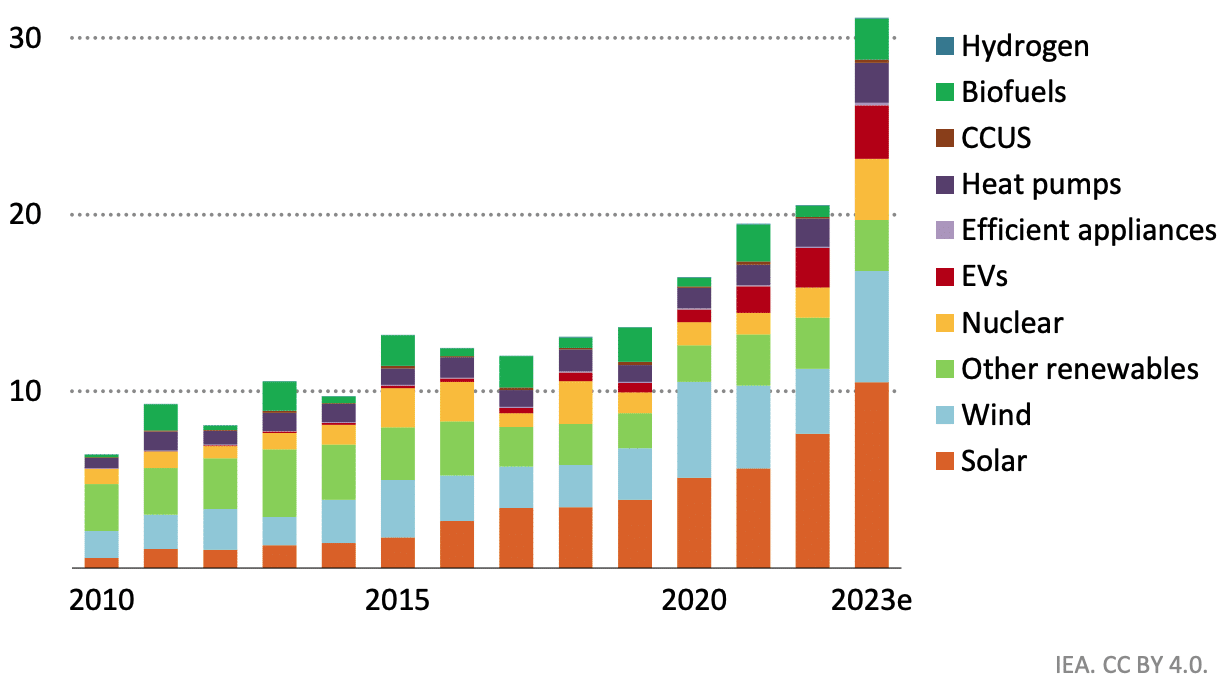

Staying on track will require all countries to move forward with net zero emissions target dates, and significant investment — clean energy spending will need to climb from the previously forecast $1.8 trillion USD in 2023, to $4.5 trillion annually in the early 2030s, the agency says.

While that is no small feat, the overall message in the roadmap update is more optimistic than the one issued in 2021.

The transition to a lower-carbon global energy system is underway — energy companies are already considering new approaches to teamwork, new models are emerging outside the CFO’s office, and technology and software are helping to take the blindfold off engineering challenges.

A key contributor to reaching net zero targets will be carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS), hydrogen, and hydrogen-based fuels.

The IEA says rapid progress is needed with CCUS and hydrogen by 2030 to reach net zero emissions targets.

The role of CCUS in the net zero emissions scenario

The IEA says there has been significant growth of clean technology deployment, but CCUS still represents a small percentage of all technologies deployed.

“The history of CCUS has largely been one of underperformance,” the report says. “Although the recent surge of announced projects for CCUS and hydrogen is encouraging, the majority have yet to reach final investment decision and need further policy support to boost demand and facilitate new enabling infrastructure.”

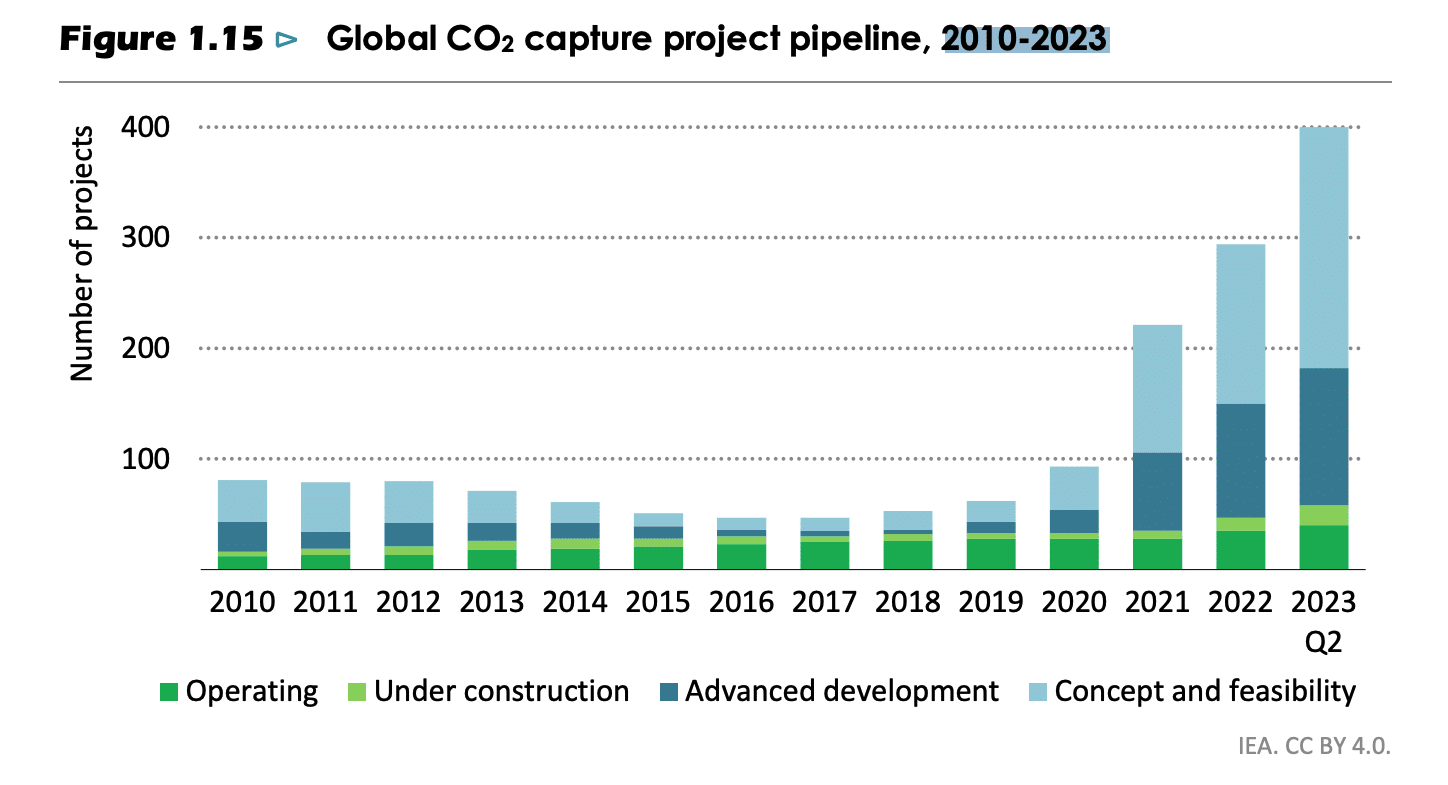

CCUS projects have been slow to deploy over the last decade, and in fact, less carbon dioxide (CO₂) capture capacity was added between 2015 and 2022 than between 2010 and 2015.

One challenge with CCUS is it needs to be tailored to site-specific conditions, and due to the scale of the solution there are fewer “learning-by-doing advances” when compared to smaller and more modular technologies, the agency says.

But a view of what’s in the pipeline offers a rosier picture, as CCUS projects tripled in 2021 and nearly doubled again since then.

The growth in CCUS projects has been spurred by policy support, namely in the United States as a result of the Inflation Reduction Act that offers incentives and tax credits to those pursuing carbon capture.

What’s needed to accelerate CCUS?

CFOs use financial models to steer business decisions toward positive outcomes; business models are used in mergers and acquisitions and for net asset value modelling; and simulation software is increasingly being used by the c-suite within energy companies to assess risk and predict financial outcomes around CCUS.

With CCUS, modelling the subsurface is the fastest and cheapest way to de-risk a project, revealing where, how, and the amount of carbon that can be stored in various reservoirs.

Today more than 45 countries have CCUS projects in development.

For Jeff Gustavson, president of Chevron New Energies, CCUS is a critical part of any net zero equation.

“It’s technology that exists today, at scale,” Gustavson said at an energy transition event in June.

Gustavson cites the company’s Gorgon project as an example of where progress is being made with carbon capture and storage.

“It abates CO₂ and it’s commercially viable in many geographies,” he said.

The Gorgon project started in 2019 and has stored nearly eight million tonnes of CO₂ in the last few years, Gustavson says.

“It is not at the capacity that we wanted to be at, and we’re working through some water management and other pressure-related issues, but we have line of sight to get into higher capacity rates. That’s a good example of a CCUS project that’s working at a very large scale.”

What’s next for Chevron and CCUS? Gustavson says the Gulf Coast of the United States is expected to be “ground zero” for CCUS for the company in the years to come.

Project timelines need to be compressed

To achieve net zero emissions targets, project lead times will need to be compressed.

CCUS projects currently take an average of six years to move from conception to the commissioning of a facility, and the IEA says that will need to be accelerated to three or four years.

One way to accelerate timelines is to run parallel processes, says Dr. Vijay Swarup, director of technology at ExxonMobil.

“We have a technology gap, and we have to do two things simultaneously,” he said. “We have to deploy technologies that are ready to be tested, and have policies and markets that can support them.”

More CCUS projects are needed in emerging markets

Developing economies are also an important piece in the emissions-reduction puzzle, and some progress has been made in emerging markets.

For example, 20 new CCUS projects were announced in 2022 in Asia and the Middle East.

China currently has less than 5% of the world’s CCUS projects under development, but the country commissioned three projects in 2023 and has a project pipeline that will increase capture capacity to 10 Mt of CO₂ each year.

In Indonesia, a legal and regulatory framework for CCUS was finalized in March 2023, representing the first of its kind in Asia.

In the Middle East, where 15% of global natural gas production takes place, there is a unique opportunity to deploy CCUS for low-emissions fuel production, the agency says. Currently the region accounts for less than 5% of global planned CCUS capacity by 2030.

“Meeting net zero emissions levels of CCUS deployment in emerging markets and developing economies requires around 130 Mt CO₂ per year of additional capture and storage capacity to start the planning stage annually from 2023 to 2026,” the IEA says. “Such a rate of deployment is ambitious given the current low number of projects in operation in those regions, but not unprecedented when compared to other sectors such as unabated cement production, coal power or oil and gas supply.”

CCUS hubs offer an opportunity to to scale carbon capture and storage

The development of CCUS hubs could accelerate success for carbon capture, as most CCUS projects to date have been managed by a single operator in order to transport CO₂ from a capture facility to an injection site — a limiting factor around scale, as risk and cost is concentrated on one company.

With CCUS hubs, shared transport and storage infrastructure that connects multiple emitters would spread cost and risk across multiple stakeholders.

“The reason for the industrial hubs right now is the business model,” said Anna Shpitsberg, Deputy Assistant Secretary for the Transition, US State Department, at an energy transition event in New York earlier this year. “There’s a lot of pieces that still need to be worked out.”

Shpitsberg says building a decarbonizing industry needs to be done on-site.

“I think it’s a lot easier to scale. So the regional hubs are seen as a pathway to get to where we might be in the future.”

The IEA report says that assessing and developing potential sites, including saline aquifers and depleted oil and gas fields, is vital because they lead to the development of other parts of the value chain, including CO₂ pipelines. In its net zero emissions scenario, the IEA says CCUS storage capacity would expand from less than 50 Mt today to around 1 Gt by 2030.

“Repurposing existing oil and gas assets, including natural gas networks, shipping terminals and offshore platforms, could help to fast track the deployment of hydrogen and CO2 infrastructure, reduce lead times and investment costs,” the agency says.

Achieving energy transition progress while balancing the increasing demand for oil and gas

Surging demand for energy is a major consideration as leaders seek to balance the need to decarbonize for the future, with the reality that people still need energy today.

In a recent interview, Dustin Meyer, senior vice president of the American Petroleum Institute, said, “Policymakers should not ignore current market realities — which are clearly signaling the need for more supply of oil and natural gas — in favor of any scenario models with predetermined outcomes.”

In its report, the IEA also suggested that fossil fuel growth will peak by 2030 — a claim that has been refuted by many energy leaders.

“This notion is wilting under scrutiny because it is mostly being driven by policies, rather than the proven combination of markets, competitive economics, and technology,” Aramco CEO, Amin Nasser, said at a recent event in Calgary.

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) echoed Nasser’s comments, saying its data-based forecasts do not support the assertion the demand will peak by 2030.

Furthermore, OPEC says predictions of declining fossil fuel demand are “dangerous” as they are often accompanied by a call to stop investing in oil and gas projects.

“Such narratives only set the global energy system up to fail spectacularly,” said OPEC Secretary General, HE Haitham Al Ghais, in a statement. “It would lead to energy chaos on a potentially unprecedented scale, with dire consequences for economies and billions of people across the world.”

The solution in an energy transition discussion is to decarbonize and reduce emissions from existing energy projects, while simultaneously meeting growing demand.

“Cognizant of the challenge facing the world to eliminate energy poverty, meet rising energy demand, and ensure affordable energy while reducing emissions, OPEC does not dismiss any energy sources or technologies, and believes that all stakeholders should do the same and recognize short- and long-term energy realities,” says HE Al Ghais.

Sign up to receive newsletter updates from Accelerate on LinkedIn.