By Pramod Jain, CEO, Computer Modelling Group (CMG)

The oil and gas industry has a branding problem with younger generations, and it has turned into a major talent problem for the industry.

Younger generations who enter universities today care deeply about sustainability, and have grown up barraged with energy transition messaging, leading to a growing perception that the world won’t need fossil fuels soon — and therefore career paths in the sector are limited.

We need to fix this, and it starts by setting the record straight.

Sustainability is important, as is the entirety of the conversation around energy transition. But the world still needs oil and gas today, and in fact, it’s only growing in demand.

Here’s the problem:

- There’s a shortage of petroleum and reservoir engineers, driven in part by fewer students graduating from university programs.

- Contrary to popular opinion, the skills and training from post-secondary programs are needed now and well into the future.

- Engineers who work in oil and gas also play an integral role in the transition to and operation of renewable energy technologies. If we don’t have people working in the industry, transition and decarbonization efforts are also at risk.

There’s a gap in educating young people about the opportunities for a bright career in the energy sector, including and especially core oil and gas competencies — which are the same skills required for carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCS); underground energy storage; geothermal energy; tidal and hydro-power energy; and critical minerals, to name a few.

But the world still needs plastic, it needs natural gas production and oil, and it will need transitional technologies for decades to come.

While graduates are shunning oil industry degrees for environmental and social reasons, careers in traditional and renewable energies must overlap and evolve together through the ESG transformation.

Students need to see opportunity beyond just transition

Two years ago, the University of Calgary suspended admissions in its oil and gas engineering program. At that time, only 10 students registered to take the course over the span of two years.

In the U.S. at Texas Tech University (which ranks fourth in the country for its petroleum engineering Bachelor of Science degree), the number of undergraduates from the program declined to the lowest in a decade.

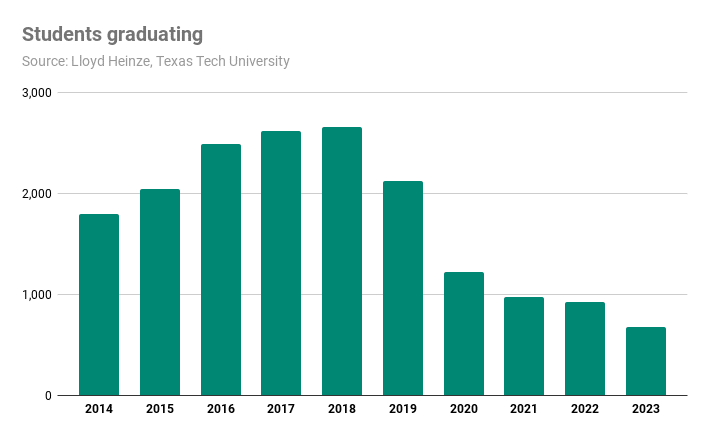

Texas Tech University does an annual survey of petroleum engineering programs, and the 25 schools that responded said they expect to graduate 655 students this year, down from the record peak of 2,615 graduates in 2017.

According to the Journal of Petroleum Technology, next year those numbers are expected to be around 500 graduates.

Here’s a look at the last decade:

Despite declining enrolment numbers, those who do graduate are getting jobs even before they walk across the stage to pick up their diplomas, or shortly after graduating.

Combined with those retiring, the fact that fewer young people are enroling or graduating in core oil and gas disciplines is brewing a perfect storm that will cause endless headaches in the energy sector.

While petroleum engineers are involved in broader functions such as designing the wells or surface facilities, reservoir engineers are narrowly focused on the subsurface. By applying basic laws of physics and chemistry, they specialize in understanding the behavior of liquid and vapor phases of crude oil, natural gas, and water in reservoir rock.

We need young people to enter the energy industry as engineers and to see just how much opportunity there is — especially as the skills they learn are transferable even through energy transition.

Natural resource engineers, technicians, and many other jobs that foster a workforce with the ability to find, develop and manage natural resources, have many things in common with conventional oil and gas industry roles.

Both the skills needed, and career path trajectories, are highly compatible.

“Many petroleum engineering and geoscience skills are transferable to areas like geothermal energy, underground energy storage (including hydrogen,) CCS and storage, offshore wind, critical minerals and rare earth elements,” write the authors of an editorial published in The Way Ahead, a publication of the Society of Petroleum Engineers.

“The petroleum engineer will also evolve as the energy mix evolves. New skills will become increasingly important, like driving product to net-zero by eliminating methane leaks and flaring, integrating renewables and storage for power generation, CCUS, energy storage, sustainability and other related sustainable development concepts,” conclude the authors, who include Rita Esuru Okoroafor, a postdoctoral scholar at the Stanford Center for Carbon Storage at Stanford University.

Industry players are working with post-secondary institutions to fix the talent gap

Many large integrated majors are adapting to the shortage by mentoring new hires and upskilling them. As my colleague Don McClatchie says, one of the greatest strengths of university graduates is their ability to learn. For large integrated oil companies, they recognize the opportunity to teach newer recruits what they need to know to do their jobs.

Meanwhile, smaller, independent energy companies who don’t have the ability to educate and retrain new hires increasingly look to technology for solutions.

We at CMG are approached regularly by organizations that want help training their workforce on simulation software to bridge the gap. Simulation technology is a key arrow in the talent quiver because it creates a shared vision of a project, so all team members — both junior and senior — are able to take part in decision making.

Technology also creates scale, so companies challenged by headcount can use it to do more with fewer people. For example, tying together real-time data and cloud computing with CMG’s reservoir software, allows one engineer in any city to monitor hundreds of wells remotely.

And as I discussed in our roundtable discussion earlier this year, the combination of simulation, data science, and machine learning come together to give you a picture of what’s below the surface, and it’s done faster than by using just simulation alone.

Now, younger generations have the advantage of technology to offset the loss of institutional knowledge and experience exiting the workforce.

In the past, these jobs would have taken five to 10 people in the field. We are expanding the training and consulting side of our business because many customers are short of engineers and seeking our help. This is especially apparent in the past 18 months.

Ultimately, the problem is a lack of new engineers replacing the ones who are leaving. Industry and universities need to update their messaging and reframe these careers as still important to society and necessary for a better quality of life.

We need to do a better job recruiting and showcasing the opportunities for a rewarding and meaningful career in the energy sector as it transitions to net zero. But more than this, we need these skills for the future and the new low-carbon technologies that complement conventional oil.

Our software multiplies the power of human capacity, but we need everyone in the industry to advocate for engineering opportunities in energy.

For younger generations or people considering working in energy, there is no better time than now. If you’re looking for purpose and want to make an impact in energy transition, energy security, or decarbonization of fossil fuels, this industry is the place to be and the timing is right now. The industry needs you.

Sign up to receive newsletter updates from Accelerate on LinkedIn.